“We will not deny to any man either justice or right.” – Magna Carta, 1215

If you visit the National Archives in Washington, DC, you will find massive doors, impressive high ceilings, granite and marble, and (usually) a reverent ambiance. Inside the somber dark sanctuary you will find the Constitution of the United States lit in the center, with the Declaration of Independence to the left and Bill of Rights to the right. It is moving. When I lived in Washington, it was about the only tourist attraction I would visit on a semi-regular basis.

A year or two ago while I was in London, I bumbled into the British Library just to see what was there and was amazed to find many fascinating artifacts from original manuscripts of the greats – from Mozart to Charles Dickens. Little did I know there was a side room with a little sign pointing to a hall with the Magna Carta. I went down the aisle and was shocked to find, with not much fanfare, multiple ancient copies of the Great Charter in this dark room.

Americans – as with most any democracy – have less reverence for old things, compared to our European counterparts. We value comfort and efficiency more, as Alexis de Tocqueville points out in Democracy in America. I know the Magna Carta and our Constitution aren’t completely comparable (Magna Carta is not exactly a constitution), but I was pleased to find how reverently we Americans treat the Constitution, as I was pleased to hear of the great celebrations in Britain today on this, the 800th anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta.

My interest in the Magna Carta started when I was in my teens and picked up a copy of How We Got Our Liberties – a 1928 history book by Lucius Swift, which I have kept and still reference often, despite its weak and torn pages. The book digs deep into the story of how our rights, particularly First Amendment rights, came to be protected by representative government, rule of law, and the due process of it. Foundational principles, as it turns out, are not developed in a lab or think-tank, but on the battlefield and in the assembly.

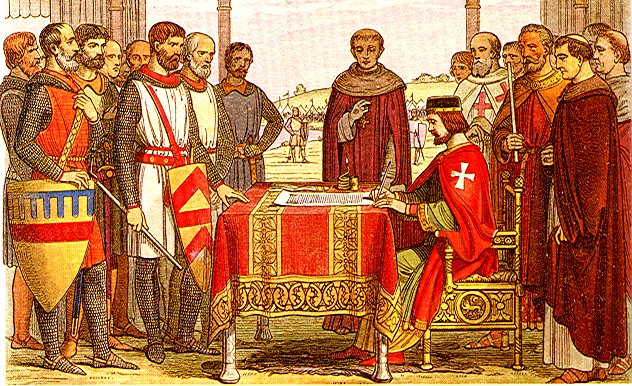

So it is with Magna Carta. The story is a bit complicated, but in short, King John had a track record of banishing subjects, instituting taxes right and left to fund his wars, and taking power through illicit means. Swift comments:

On one side was the king of a nation who had trampled her laws under foot, had taken away the liberties of his people, had plundered them and had broken down every defense they had against arbitrary rule. On the other side were the representatives of the people demanding from the king the restoration of the laws of their forefathers. They risked everything. If they failed, every one of them would lose his head and his estates. Of all the men who have since faced danger for the benefit of people of the English-speaking race none is entitled to a more grateful remembrance.

That reminds me a lot of the Founding Fathers. The sixty-two paragraph document laid the groundwork for more than the famous “rule of law.” Though that was the central idea, and the central principle of the American system, our Founders even gleaned phrases such as “taxation without representation” from the Great Charter. The risk taken by the barons must have inspired the Founders to stand united against injustice.

There are a few lessons I wish to draw from the story as inspiration of us today.

- If the barons had not stood firm and united, the movement would have undoubtedly failed, and they all would have suffered greatly. You will do great things when you stand united for justice.

- After reading the demands of the Great Charter, the King is said to have said something to the effect, “If I accept this, I will become a slave.” Yes. As steward of the people, government officials should rightly be revered and not scorned if he (or she) is just; but to be a great leader, he must be a slave to the people and have the commonwealth at heart.

- The principle of rule of law is a foundational one – and one our ancestors paid dearly for. We should not flippantly ignore offenses towards it, as, without it, we will certainly lose the rest of our rights.

- The priest Stephan Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, deserves much credit for brokering the deal between the barons and King John, and probably authoring much of Magna Carta. His biblical principles assuredly informed him, and, further, the role of faith cannot be downplayed in the history of the Charter. Like Langton, we should not shirk from biblical principle informing our politics.

It is good of us to reflect on the Great Charter today. “Magna Carta is the being of our being,” quipped Thomas Tany, an influential preacher, in 1650. William Pitt the Elder called it, “The Bible of the English Constitution,” and others “a symbol of the struggle against tyranny.” Still others, “a reference to which we should always return to ensure that we are proceeding in the right direction.” Or Winston Churchill, who called it a “reaffirmation of a supreme law.”

So I ask, what will you do that might be celebrated centuries from now? I can only imagine the surprise of those involved in Magna Carta, which was born out of immediate need and has lasted nearly a millennium. The Charter was a great step towards protection of life, liberty and property, but for centuries has endured attack from less enlightened officials. Protection of fundamental rights is, indeed, an ongoing war.

I submit that you needn’t write your own Great Charter to leave a legacy. Our task is the more monotonous one – the less dangerous, but equally important task of maintaining the principles embodied in foundational works, such as the Magna Carta.